Purchase A Brief Natural History of Women!

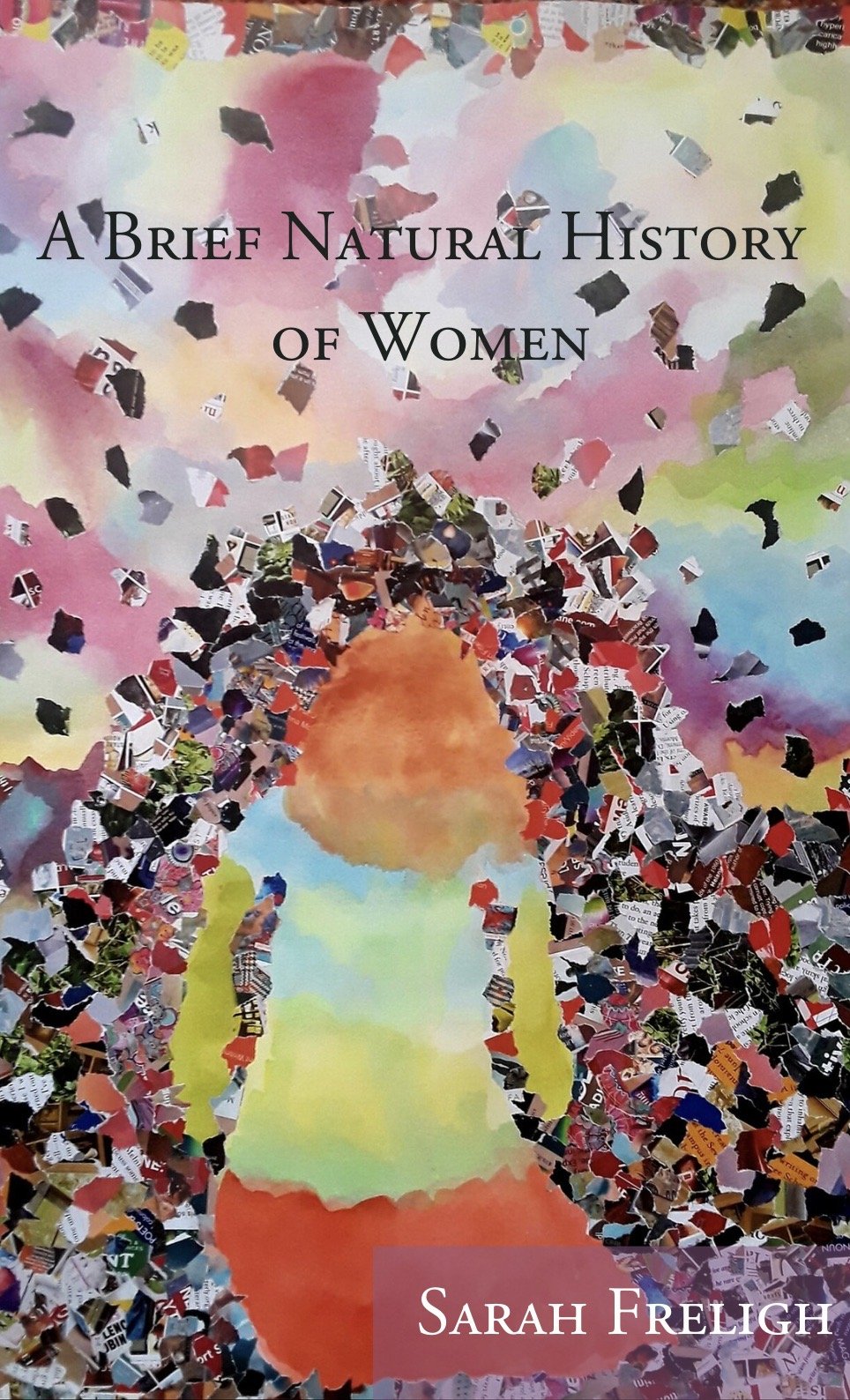

Cover art: I Walked Away and Started a New Life, Stacy Russo

Praise for A Brief Natural History of Women:

Readers of Jayne Anne Phillips and Amy Hempel will fall in love with A Brief Natural History of Women, Sarah Freligh's forceful and unforgettable new flash collection. Set in and around Detroit, her hard living characters may wish they "could unzip [them]selves and wear the dull side out," but it is precisely how they embody their grief and grit and rage that make for such hard hitting stories. Freligh is a singular stylist and queen of compression whose work takes up boundless space in our hearts.

—Sara Lippmann, author of Lech

In A Brief Natural History of Women, Sarah Freligh’s girls and women grieve, rant, stumble and topple, pour each other shots, desert each other, catch each other mid-fall; they are in equal parts desperate and resilient, weary and philosophical. “How we’ll wish we could unzip ourselves and wear the dull side out,” one girl opines. This is a dazzling, acute, spiky book by one of the best flash fiction authors writing today.

—Kim Magowan, author of How Far I’ve Come

Sarah Freligh’s stories are crisp and bright and melancholy, with all the senses engaged. “The tidy lima bean of uterus” illustrates a lesson on sex where students are encouraged “to hush the yes in our girl bodies.” Beer is not just beer —it has “enough foam to mustache your upper lip . . . enough sparkle to scald your throat”—and comes with a metaphor riding on it that describes the narrator’s love life.

The stories glimpse into the lives of their narrators, each a marvel of construction—small and perfect, but with jagged edges. The settings are places of transience—bars, train stations, etc.—where these midwest, working class, beer-drinking characters are “headlights on a wall, there and gone,” broken, yes, but vivid and ready to engage with life. A number of them are in first-person plural, we-stories that are a communal knowing, women’s voices coming together to say, this is what we know, to our sorrow. As Kate says in “Mad,” the final story: “And, oh, what a wild bird can do when set loose . . . Such madness. Such damage.”

—Mary Grimm, author of Stealing Time

Sarah Freligh is the author of five books, including Sad Math, winner of the 2014 Moon City Press Poetry Prize and the 2015 Whirling Prize from the University of Indianapolis, and We, published by Harbor Editions in 2021. Recent work has appeared in the Wigleaf 50, New Micro: Exceptionally Short Fiction (Norton 2018), Best Microfiction (2019-22), and Best Small Fiction 2022. Among her awards are poetry fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Saltonstall Foundation.